Biowarfare in the Restroom: Mitigating Toilet “Sneeze”

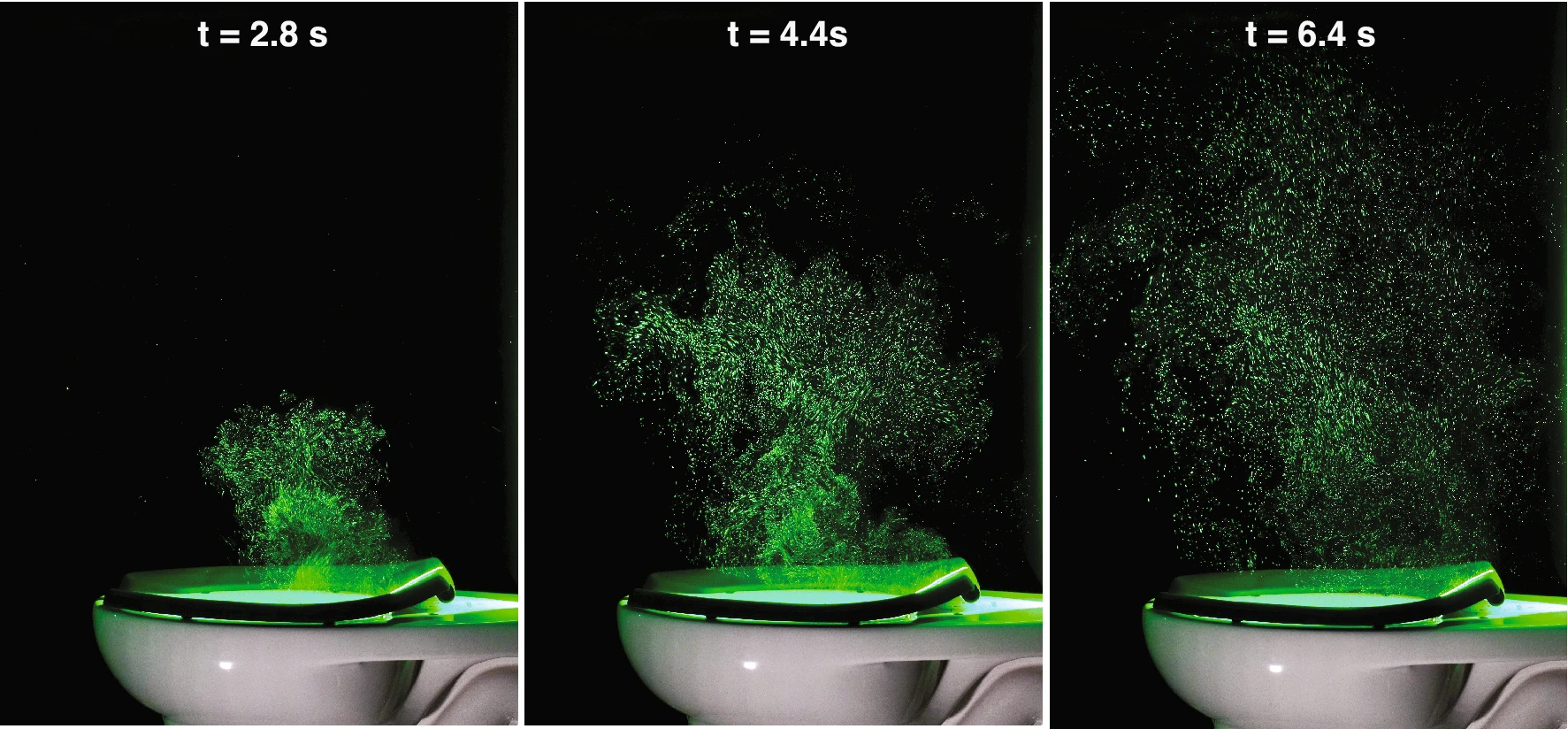

It’s with good reason that historically the most effective delivery method for biological warfare weapons is via aerosol suspensions: finely divided droplets or powders containing bacteria may be carried by air currents for long distances spreading their contamination as they are inhaled or fall on surfaces to be picked up later by touch. Also, the aerosol droplets are so small (diameters less than 0.0002 inches) that they can’t be seen by the naked eye without special lighting effects and so the spread of contamination can’t be easily detected.

When humans sneeze they produce biological warfare weapons of their own: aerosols containing aqueous droplets enriched with a wide variety of the bacteria found in all human respiratory systems. The aerosol droplets are about the same size as those used for biowarfare.

Most people have enough sense not to sneeze without covering their nose and mouth briefly. But in restrooms there’s another source of powerful biowarfare weaponry that is not recognized by many people.

From pioneering work done by microbiologists nearly 70 years ago, it has been known that flushing of many types of toilets produces bacteria-bearing aerosols with droplet sizes closely approximating those from human sneezes and military bioweapons. It’s natural that this has been given the unappetizing name of “toilet sneeze”. The original microbiological results were extended in a scientific paper [1] that showed that within 2 hours after a single flush of this type of toilet in a 36 ft2 restroom, bacteria could be found randomly distributed throughout the restroom surfaces. That is, the bacteria-containing aerosol droplets from toilet sneeze remain airborne for relatively long times before coming to rest on—and contaminating—both horizontal and vertical surfaces. Unless removed immediately, and that is almost never done, the fallen aerosol droplets from toilet sneeze dry on the surfaces.

It has also been shown by microbiologists that bacteria found dried on surfaces may remain viable (that is, can still be infectious) for days, weeks, and even months after they have been deposited on the surfaces by aerosols such as those from toilet sneeze. Also, dried bacteria on surfaces may be picked up by air currents and vibrations and become re-aerosolized as infectious particles in restroom air.

Since human solid waste is known to contain many hundreds of different species of bacteria, many of them pathogens (species that cause disease in humans and animals), toilet sneeze is a very efficient way of spreading potentially dangerous bacterial contamination all over restrooms, especially in multi-stall public restrooms. Unless removed efficiently or killed by disinfection, the bacteria in the dried aerosols may remain viable for a long time.

The question is how can this toilet sneeze-caused contamination be minimized?

Closing the lid before flushing may or may not be helpful, and in most commercial restrooms, there is no toilet lid.

The only adequate bacterial mitigation procedure is one that ensures with quantitative post-cleaning data that contamination has actually been removed to a desirable level. That is, an adequate procedure is one that integrates cleaning, disinfection, and microbiological measurement. Integration of a cleaning process with measurement of the microbiological outcome of the process is the basis of one part of the concept of ICM (Integrated Cleaning and Measurement) that was introduced to the cleaning industry by the director of the Indoor Health Council and Kaivac.

Kaivac No-Touch Cleaning™ spray-and-vac systems include disinfectant metering and injection in a pressure washer with a vacuum system specifically targeted at restroom cleaning. When used with a rapid bacterial detection instrument such as Kaivac’s SystemSURE PLUS ATP palm-sized unit, the combination forms a powerful ICM process. An additional advantage of this bacterial detection system is that the data collected can be stored in a computer to form part of a permanent record of cleaning efficiency.

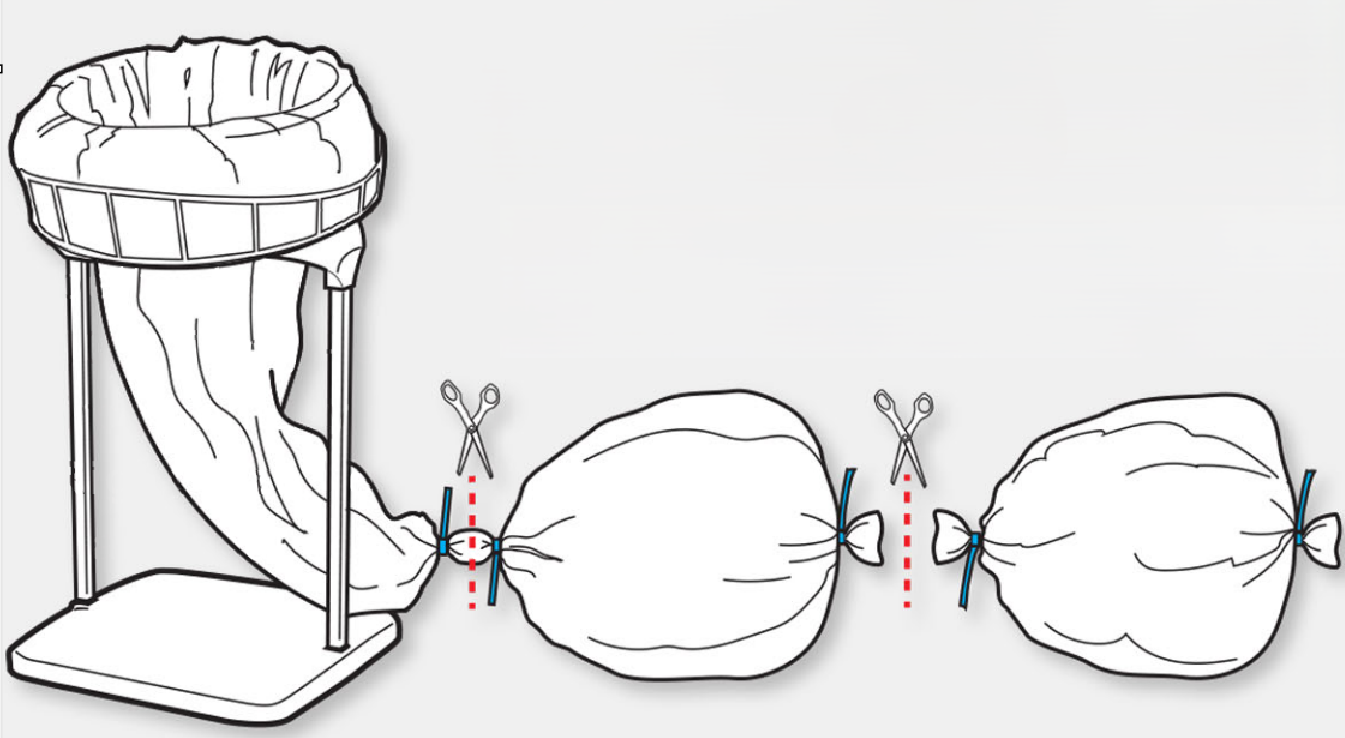

Efficiently removing dried bacterial contamination from tiled public restroom floors with grouted joints is an especially difficult task because the contamination enjoys the protection of the rough grout surfaces. However, it has been quantitatively shown that the Kaivac spray-and-vac process where fresh cleaning and disinfecting solution is continuously applied to tiled bathroom surfaces and subsequently extracted into a waste container is at least 60 times more effective in reducing bacterial contamination from grouted tile restroom floors than conventional wetting and wringing cleaning cycles [2].

The phenomenon of toilet sneeze and the lingering contamination it can cause in restrooms needs to be more fully recognized by the cleaning industry along with the advantages of implementing the ICM model to meet this contamination challenge[3].

[This post adapted from an article by Dr. Jay Glasel.]

Older References

[1] Gerba, C.P., Wallis, C., Melnik, J.L. (1975) Microbiological Hazards of Household Toilets: Droplet Production and the Fate of Residual Organisms, Appl. Microbiol. 30 229-237.

[2] Glasel, J.A. (2008) Cleaning Methods for Ceramic Tile Floors, Cont. Environ. 11 19-22.

Recent References

[3] Crimaldi, J.P., True, A.C., Linden, K.G. et al. Commercial toilets emit energetic and rapidly spreading aerosol plumes. Sci Rep 12, 20493 (2022)

Image Creative Commons License 4.0 w/o changes.