Shoot for the Moon Training, Cleaning for Health

“Shoot for the moon. Even if you miss it you will land among the stars.”

— Les Brown

When motivational speaker Les Brown said the words above, he likely wasn’t thinking of training school custodians.

“Our janitors are lame!” 18-year-old Jimmy Buxtor — son of the facility director at his high school in southwest Georgia — told his Dad, Bruce, over breakfast. “Our restrooms stink! Why don’t they take pride in their work?”

“I don’t have all the answers.” Bruce smiled, sipped his coffee, glanced at the “Be the Change” tattoo on Jimmy’s right hand, then at the anchor tattoo on his own wrist. “What do you think we should do about it?”

“I don’t know — Something… Anything!” Jimmy stabbed at his waffle.

At heart, Jimmy was an activist, and Bruce a proud single parent, but they could not have been more different in appearance or style. Jimmy’s sandy hair was shoulder length, while Bruce — a former naval engineer who had served on a carrier in the Persian Gulf — looked like Val Kilmer in Top Gun.

“Ok, come to our meeting today at 10am,” Bruce said, checking his watch.

“I will.” said Jimmy, locking eyes with Bruce.

He had his mother’s fire.

Thirty-five Georgia school facility leaders, several spouses, and one student — Jimmy — met during Fall Break in band-practice room 3B on the first Monday in October.

Bruce and Jimmy entered the room; Bruce wearing a blue polo tucked in beige khakis breaking ¼-inch above rubber-soled Rockports, and Jimmy in a black T-shirt — with “CHANGE!” in the front and “NOW!” on the back in red letters — draped over black sweats bunching on Nike high-tops.

Jimmy saw the “Make Music Not Noise” sign on the front of the lectern — set off by musical notes at beginning and end — looked around at the silent group, and smirked.

Knowing the look, Bruce whispered:

“You ok?”

“Fine…” But some “noise” might help this group, he thought, recalling the Stanford students who, in 1995, called attention to censorship issues by revealing a body part that, ironically, had to be censored in newspaper photos. [In May 1995, Stanford University students staged a “mass mooning” in protest of censorship in the media – Wikipedia]

Bruce and Jimmy donned ”Hello” name tags, threaded past several music stands and sat at the middle of the second to last row.

The first speaker — a risk management expert — droned on about safety for an hour using three slides.

“Facility safety is a byproduct of 20 elements that every manager should understand and apply … Number 15 [at the end of slide two] is Georgia’s ‘Rules and Regulations for the State Minimum Fire Safety Standards’ … promulgated to establish the State’s minimum fire safety standards specified in the Official Code of Georgia Annotated (O.C.G.A.) Section 25-2-4 available at this web address…”

Bruce snored lightly, snorted in response to Jimmy’s elbow, straightened, look at the wall clock behind the speaker, and refocused.

Perry Shimanoff, a cleaning consultant — who would be the first speaker after lunch — sat in the row behind them, amused.

The department of education speaker was next, regaling the group with seven slides — all spreadsheets.

“This is nonsense!” Jimmy whispered to Bruce, who shushed him with a finger to his lip.

They broke for lunch, but Jimmy had a plan.

After lunch, Perry, a wiry, former marine with thinning grey hair, black-rimmed glasses, tie and button-down shirt, stepped up to the podium:

“I brought some post-lunch wakeup activities,” Perry said, pointing to a table on his right holding several microfiber towels, a trigger sprayer, a combination white light/UV flashlight, and an ATP meter; a device that measures organic soil — i.e., germs and germ food — on surfaces.

Farther right stood a black machine that, while resembling a rolling mop bucket at its base, had an attached floor squeegee, top-mounted tank, vacuum and other attachments.

“May I have a volunteer?”

Perry waited several seconds.

No response.

Jimmy looked around — left, right, front, back.

Still nothing.

“Sheesh!” He whispered, raised his hand, and rose when Perry motioned him forward.

He walked up the center aisle, stopped before the lectern, took a deep breath, smirked, and — in a single motion…

…lifted his shirt, dropped his pants and bared his buttocks to the room.

Three spouses gasped. Bruce was clearly awake.

Jimmy pulled up his sweats, stood still, and looked at Perry.

The room was quiet.

Perry broke the silence:

“Jimmy, did you know mooning is a misdemeanor in the state of Georgia, and a felony in some states…?”

Jimmy smirked.

Perry looked slowly around at the group, then at Jimmy.

“…Still, your disruptive actions today flag an even bigger crime. Do you know what that is?”

“Not really.”

Perry pushed up his glasses, locked eyes with Jimmy, and said: “Obscenely-poor cleaning.” — then, deadpan — “It’s time we got to the bottom of matters, don’t you think?”

Laughter erupted. Jimmy smiled.

“Shall we begin?”

Perry joined Jimmy at the activity table, picked up, held high, and panned left-to-right the “ATP Meter” sign, then did the same with the ATP meter before handing it to Jimmy.

After using his arm to drag items to one side of the table, Perry returned to the podium and asked Jimmy to look at the tabletop.

“Is it clean?” he asked.

“Looks good to me.”

“Ok. Let’s take measurements.”

Perry went to the table, gave Jimmy five fresh swabs, demonstrated their use, then had him sample five 4” x 4” spots using the ATP meter — a process that would take five minutes — and average the readings.

Back at the microphone, Perry described the Six Steps of Smart Cleaning:

1. Identify the Soil

2. Pickup

3. Package

4. Dispose

5. Inspect

6. Measure

“Speaking of #6, ‘Measure’ — Jimmy, what does ATP measurement show?”

“The average is 1,066,” Jimmy said, tapping the calculator on his phone.

“What does that mean?”

“No idea.”

“It refers to relative cleanliness, or in this case, the lack of it,” Perry said, explaining ATP was adenosine triphosphate — a molecule found in organic matter that could contain or host germs — and measuring ATP before and after cleaning showed changes in cleanliness. “High numbers may mean failure, depending on the application.”

“Jimmy, please clean the table.”

“Sure. With what?”

Perry pointed to a trigger-spray bottle of disinfectant and a yellow microfiber cloth.

Jimmy sprayed the table, scrunched the cloth, and lazily wiped the clean-looking table.

Perry handed him five more fresh swabs.

“Please take another set of readings.”

“Ok.”

Looking toward the audience, Perry said: “Can I get a volunteer to read a handout?”

Bruce raised his hand, came forward, and began reading the sheet on the lectern: “Professional cleaners need to know what health issues there are in the indoor environment. Understanding health issues helps us to define our business and to justify our services and our rates—”

“Excuse me, Bruce, would you speak up a bit?” Perry stood behind him on the podium.

Bruce started again: “Professional cleaners need to know what health issues there are in the indoor environment. Understanding health issues helps us to define our business and to justify our services and our rates—”

“Better!” said Perry. “Please continue.”

“The value of the health benefit increases the value of the service—”

“Louder please.”

“The value of the health benefit increases the value of the service—”

“Bruce, even louder please…”

Bruce repeated in a near shout: “The value of the health benefit increases the value of the service!”

Jimmy had taken three samples, but stopped, enthralled.

Perry smiled and gave Bruce a bottle of water.

“Thank you Bruce. Please be seated.”

“‘The value of the health benefit increases the value of the service,’” Perry repeated. “Who wrote those words and when?” He pulled a book from the shelf below the microphone, held it up, and said: “Dr. Michael Berry wrote ‘Protecting the Built Environment – Cleaning for Health’ in 1994.”

Perry read from it:

“Cleaning is the science of controlling contaminants. It is one of the most basic ways we manage our environment. To fully understand cleaning science, we need to understand both how it is scientific and how it is related to the larger discipline of environmental management.”

“Speaking of science, Jimmy, what is your latest reading?”

The average is “478.”

“Is the table clean?” Perry asked the group, as he clipped a lavalier mic to his shirt.

“No!” At least, they were awake.

Perry joined Jimmy at the table, picked up a green microfiber towel, folded it into quarters, applied cleaner, and flipped it after each few swipes to wipe the table using all eight surfaces of the towel, four per side.

“Please take measurements.”

Jimmy nodded.

Perry turned on a flashlight, placed the cloth Jimmy used over the lens, and pointed it toward the audience. “What do you see?”

“Light.” Someone said.

Perry then put the green cloth over the beam and showed it blocked the light.

“Which is the better cloth?” Several people pointed at the green one.

“Right.”

Perry pulled a tub of margarine from the soft-sided cooler where he stored ATP swabs, removed the lid, swiped a finger across the oily surface and applied a circular film to a classroom window.

He pointed to the window smear. “What will remove this?”

“A degreaser?” Someone volunteered.

“Good answer, but…” He folded a fresh green cloth into quarters, applied water, made four passes using two sides of the cloth, invited others to look for residue on the glass — and there was none.

“How is this possible?” Perry asked rhetorically.

He paused and continued:

“Using all sides of the cloth woven with dense, super-fine fibers boosts surface area, removes micro-particles, oils, and even bacteria without chemicals.”

“Anyone had funky smelling damp rags?” Half of the group raised their hands.

“That’s from bacteria and mold.”

“Silver strands in this cloth…” — he pulled it through the circle of his thumb and forefinger like a magician with a handkerchief — “…will inactivate microbes in the cloth; no chemicals needed.”

“Jimmy, what did your measurements show after use of the green cloth on the table?”

“The average was 30.” Jimmy panned the meter’s last LED readout of “28” left to right toward the audience.

“Bruce, would you go to the men’s room?”

“Sure. What for?”

“To answer nature’s call,” Perry smiled. “More importantly, tell us what you see and smell.”

Bruce left.

Perry read from Dr. Berry’s book, concluding with:

“Cleaning is the process of removing pollutants from the environment and putting them in their proper place … In cleaning, we find, identify, capture, contain, remove, and dispose of pollutants … Cleaning is removing.

Perry took a drink of water.

Bruce returned.

“What did you find?”

“Everything looked good. It smelled of pine oil.”

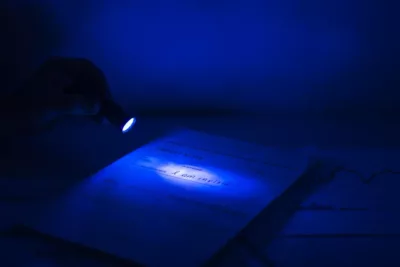

“Ok. Take this UV flashlight and go back to the restroom, turn off the lights, point the UV light at the floor, then come back and tell us what you see.”

“Will do.”

“Jimmy, please roll the black cleaning machine front and center.”

Bruce returned only moments later.

“There were glowing yellow-green spots in the floor grout.”

“Urine contains phosphorus which fluoresces,” Perry said. “Bacteria eat it, grow in it, and produce odor. It’s also acidic and can harm grout. Beyond the obvious reason, why is there urine on the floor?”

“We’re not removing it,” Bruce said.

“Thank you. So, how can cleaning, or the lack of it affect health?”

He held up a report with the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Logo on the cover, and read:

“Cleaning reduces germs on surfaces and lowers risk of infection, and in most situations, cleaning alone removes most viral particles with the potential of a 90–99.9% reduction of microbe levels with proper cleaning.”

“Let that sink in.”

Perry looked at Bruce: “For the record, the restroom floor you inspected was mopped an hour before you arrived.”

“Is mopping a removal method?”

“No, not completely,” A director in the front row responded.

“Right.”

Perry pointed toward the black machine and said:

“This is a dispense-and-vac system, and it’s better at removing dirt and germs than mopping; even with plain water. How? It dispenses liquid to the floor, enables the user to agitate it, then removes suspended soil by vacuuming.”

“Bruce, would you care to try it in the restroom?”

“Yes.”

“Ok, watch the training video on the machine’s LCD screen before you start.”

Bruce grabbed the UV light and rolled the machine out the door.

Perry continued reading from Dr. Berry’s book.

Bruce returned 15 minutes later.

“Nothing was left on the floor.” He pointed at the UV Light while rolling the machine back to its place right of the table.

Jimmy stood by the table — thoughtful: Cleaning science? Cleaning for health? Tools that eliminated the need for chemicals? Good stuff!

Perry concluded by re-emphasizing the importance of those who clean, and as the room emptied, Jimmy approached and apologized for mooning the group.

“It’s ok,” Perry said. “You woke everyone up.”

Jimmy asked about getting certified to teach the material.

“Great idea.” He gave Jimmy an invitation to attend the upcoming custodial and train-the-trainer workshops at Georgia’s SouthPark University.

“Please read this before you come.” He handed Jimmy a comb-bound custodial handbook from the lectern shelf.

“One more thing.” Perry looked sternly at Jimmy. “When you arrive at the training room, during the event, and at all other times, except when using the men’s restroom — please do keep your pants up.”

“Let’s shoot for the moon with our training and cleaning goals, shall we?”

“Right.”

Bruce was proud.

This was activism through education.

We welcome input on this topic.